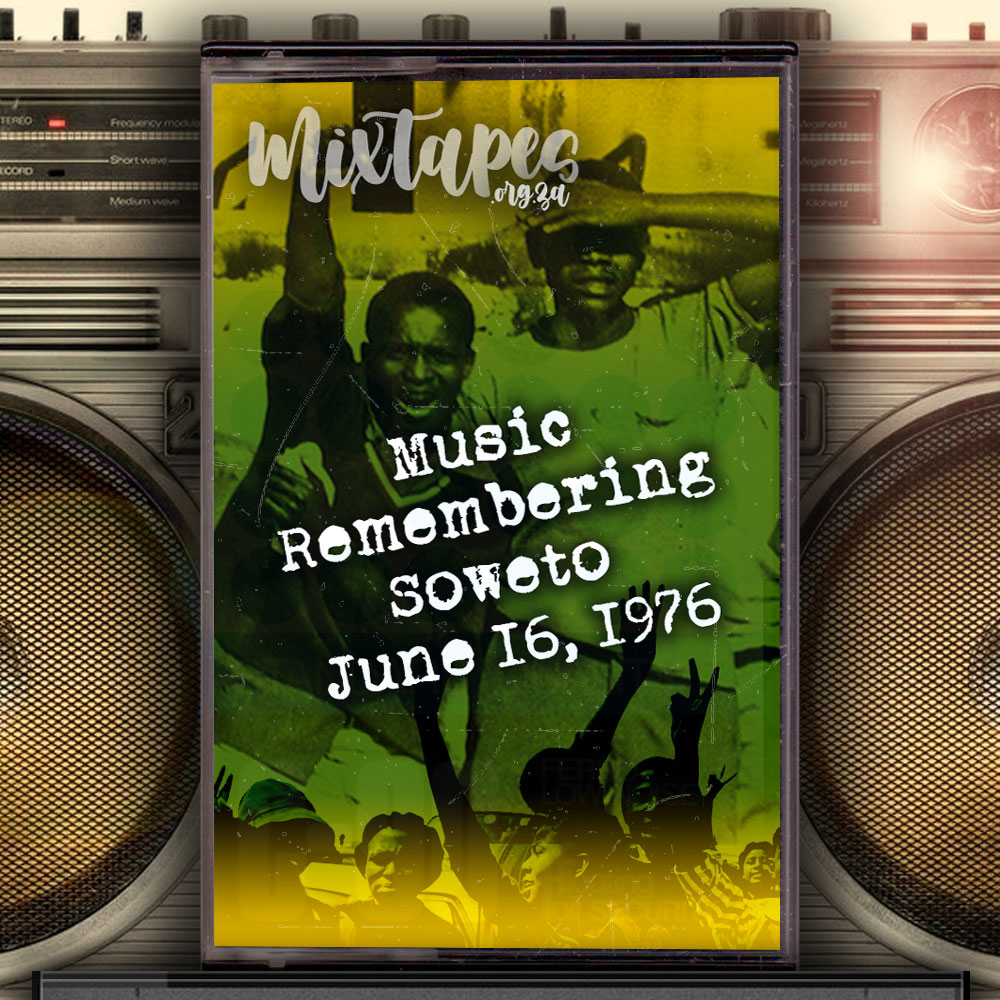

June 16th is Youth Day in South Africa, a day which commemorates June 16th 1976, when, on a wintery Wednesday morning, between 10 000 and 20 000 Soweto school children marched against the apartheid government’s decision to force school children to be taught half their subjects in Afrikaans. The police used violence to stop the protest and many students were shot, injured and killed. The uprising quickly spread across South Africa and developed into a protest against Bantu Education in general.

June 16th became a landmark date, after which resistance to apartheid gradually spiralled, despite government attempts to suppress it. Like Sharpeville at the beginning of the previous decade, Soweto June 1976 sent shockwaves through South Africa and the rest of the rest of the world, and musicians wrote songs in protest, in solidarity and in commemoration.

Among the first musicians to respond was South African musician in exile, Hugh Masekela, who penned the powerful “Soweto Blues” (released in 1977). Others who were quick to react included South African folk singer, Paul Clingman, whose commemorative song, “Anniversary Of June 16” was released in 1977, Nigerian Sonny Okosun’s whose “Fire In Soweto” was also released in 1977, South African exiled cultural ensemble, Jabula, whose “Soweto’s Children” was released in 1978, and Edi Niederlander, whose “Bitter Fruit” was written and performed soon after the event, but only recorded when she negotiated her first recording contract in 1985. “Farwell, Embers Of Soweto” by the Amandla Cultural Group was written and performed in the late 1970s but released as part of a live album in 1982.

Many protest and commemorative songs were released over the next few decades. In the 1980s these included Billy Bragg’s moving cover of Sweet Honey in the Rock’s “Chile, Your Waters Run Deep Through Soweto”, performed for the John Peel Sessions in 1986, Jeffery Osborne’s “Soweto” (1986), Stimela’s “Soweto Save The Children” (1987), “Soweto – So Where To?” by the Mamu Players (From the Township Boy musical, released by Shifty Records in 1987), Super Diamano De Dakar’s “Soweto” (1987) and Max Adioa’s “Soweto Man” (1989).

The K-Teams’ “June 16” was also performed in the 1980s but released by Shifty Records in 1990. Other 1990s releases included Brenda Fassie’s “Shoot Them Before They Grow” (1990), Dolly Rathebe & the Elite Swingsters’ “Blues For Soweto” (1991) and Sipho Mabuse’s “Suite June 16” (1996).

Commemorative releases have continued into the 21st Century, including Baba Shibambo’s “Remember June 16, 1976 (Soweto Uprising)” (2004) and Jimmy Dludlu’s “June 16th (2007). Some of the Soweto June 16th releases from the past two decades have included a comparative dimension, such as Joy Denalane’s “Soweto ’76 – ’06” (2006), Simphiwe Dana’s “State Of Emergency” (2012) and “Uprising 16 June 1976” by OLU8, MXO, SimeFree, Don Dada, Nyiwa and Lady Presh (2021).

In particular, Simphiwe Dana draws a comparison between conditions facing the youth of 1976 and those confronted by today’s youth. Despite the overthrow of the system of apartheid, the current government has let down today’s youth: the public education system is in tatters and unemployment is growing. For many of today’s youth it is a dry black season with little to celebrate. As much as we take pause to remember the youth of 1976, we need to recognize that the struggle continues …

- Soweto blues – Hugh Masekela

- Bitter fruit – Edi Niederlander

- Anniversary of June 16 – Paul Clingman

- Chile your water run deep through Soweto – Billy Bragg

- June 16 – The K Team

- Soweto – so where to? – Mamu Players

- Shoot them before they grow – Brenda Fassie

- State of emergency – Simphiwe Dana

- Soweto ’76 – ’06 – Joy Denalane

- Soweto – Jeffery Osborne

- Remember June 16, 1976 (Soweto Uprising) – Baba Shibambo

- Soweto save the children – Stimela

- June 16th – Jimmy Dludlu

- Blues for Soweto – Dolly Rathebe & the Elite Swingsters

- Soweto – Super Diamano De Dakar

- Suite June 16 – Sipho Mabuse

- Fire in Soweto – Sonny Okosun

- Soweto man – Max Adioa

- Uprising16 June 1976 – OLU8, MXO, SimeFree, Don Dada, Nyiwa, Lady Presh

- Soweto’s children – Jabula

- Farwell, embers of Soweto – Amandla Cultural Group