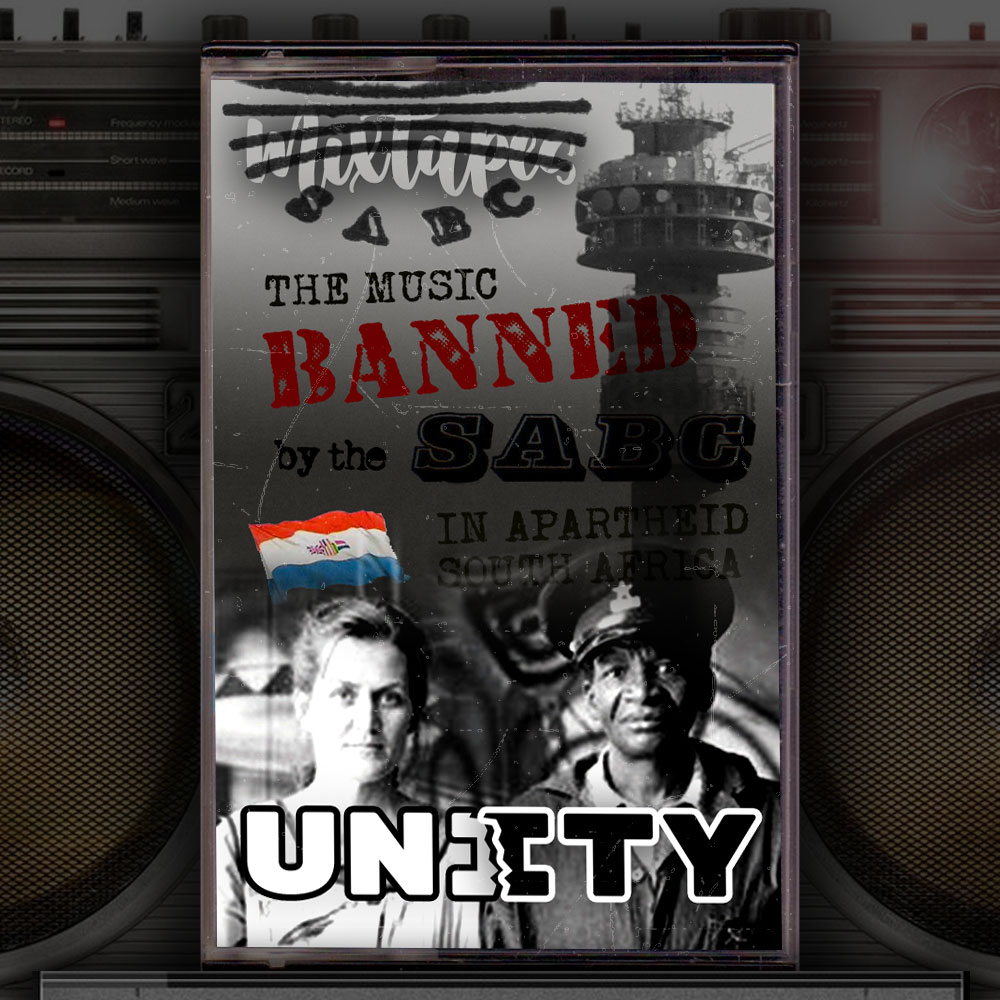

A core aspect of apartheid was to keep people apart in order to provide them with unequal resources and to treat them inequitably. There were separate areas to live in, separate buses, cinemas, park benches, public toilets, libraries, beaches, schools, hospitals, radio stations and on and on. Furthermore, the Immorality Act made it illegal for people of different races to have sex with each other, let alone get married. This mixtape delves into the SABC censors’ attempts to stop racial mixing as much as was in their stifling power to do so.

The SABC censors’ extreme paranoia about racial mixing led to the banning of politically innocuous songs like the Gladys Knight and the Pips cover of the Beatles’ “Come Together” because they believed that the lines “One thing I can tell you is you got to be free, come together right now, over me” could be interpreted to be about freedom from apartheid separation and about people of different races coming together (and that’s not even sexually). However, most of the songs banned from airplay for calling on racial unity were more overt. This included several songs which referred to inter-racial dating and god forbid, inter-racial sex.

Examples included on this mixtape include “Melting Pot” by Blue Mink which included the lines “What we need is a great big melting pot, big enough to take the world and all it’s got, keep it stirring for a hundred years or more, and turn out coffee-coloured people by the score.” The apartheid mind surely boggled. As it surely did with “Black Boys” from the Musical Hair soundtrack, which, like “Melting Pot” was also banned by the Directorate of Publications. The singers, including white women, profess that: “Black boys are nutritious, black boys fill me up, black boys are so damn yummy, they satisfy my tummy, I have such a sweet tooth, when it comes to love.” These sexual expressions did not go down well with prudish and racist 1960s apartheid sentiments.

Similarly, Gino Vanelli’s “Mama Coco” was overtly about sex between people of different races, while also managing to rhyme ‘anticipation’ which ‘Caucasian’: “I love you Mama Coco … Mama Coco such anticipation, Mama Coco, mam you’re blowing my mind, Mama Coco I’m just a male Caucasian, Mama Coco I’m a virgin to your kind.” A similar theme was explored in “Do It Anyway” by John Miles, but far less overtly: “I’m gonna do it anyway, it doesn’t matter what the people say, and in the end you all will see, the only one who’s right is me. In my own mind, she’s the right kind, even though her colour scares you, try to see straight, it’s never too late, maybe see the light of day”.

Meanwhile, Boy George’s “Girl With Combination Skin” was about inter-racial dating: “Her mother called her angel, so imagine her surprise, when she walked into the party, with a black boy at her side”. In “Basin Street Blues” the Dorsey Brothers sing of inter-racial fraternizing: “That’s where the white and dark folks meet, a heaven on earth, they call it Basin Street”, while in a cover of Freedom Children’s “Tribal Fence” Rabbitt and Margaret Singana gave the censors some worrying images to ponder censoriously upon: “Say you are my lover,

say you are my child … When will we be, past tribal fence and family tree”.

It was not only inter-racial sex and dating which caused the SABC censors to reach for the ‘avoid’ stickers. Songs which promoted inter-racial harmony in general were also frowned upon, particularly before the mid to late 1980s when various reforms meant that selected petty apartheid laws were relaxed and not all racial mixing was illegal. The political changes meant that by the mid-1980s there seems to have been a degree of confusion among the SABC censors who banned some songs about racial harmony while others with a similar theme were allowed airplay. An obvious example is “Ebony And Ivory” by Paul McCartney and Stevie Wonder which became a hit on SABC stations, and the government’s own Bureau for Information propaganda song – “Together We’ll Build A Brighter Future” – which could well have been ‘avoided’ given that it was so terrible, but the SABC played it regularly for a while because of government orders and probably because they got paid to play it (anyone with information about this please step forward!).

All that aside, some songs were nevertheless banned from airplay simply because they called on people to come together, even without any mention of race or ethnicity. For example, back in 1966, in “Get Together”, Julie Felix sang “Come on people now, smile on your brother, everybody get together, try to love one another, right now”, and just over a decade later, “One Love” by Bob Marley & the Wailers was also prohibited from airplay for including lyrics like “One love, one heart, let’s get together and feel all right.”

However, the censors were most troubled by songs which specifically called for racial unity. For example, Janis Ian’s “Society’s Child” was problematic in the rigid apartheid days of 1960s South Africa, as it explored friendship across races and questioned racial prejudice: “Walk me down to school, baby, everybody’s acting deaf and blind, until they turn and say, ‘Why don’t you stick to your own kind?’ My teachers all laugh, their smirking faces, cutting deep into our affairs, preachers of equality, think they believe it? Then why won’t they let us be?”

In the early 1970s, in “All Kinds Of People”, Burt Bacharach also called for inter-racial unity in the face of racial prejudice: “Light kind of people, should feel compassion, for dark kind of people, should feel compassion, and care for each other. All kinds of people, should reach out, and help one another”. Very similarly, and just one year later, Timmy Thomas (in “Why Can’t We Live Together”) sang: “No matter what colour, you are still my brother, everybody wants to live together, why can’t we be together?” Three Dog Night’s cover of “Black And White”, also from 1972, called for racial unity: “The world is black, the world is white, it turns by day and then by night. A child is black, a child is white, together they grow to see the light.” And in 1975 War released “Why Can’t We Be Friends” with the lines “The colour of your skin don’t matter to me, as long as we can live in harmony.” Along with the rest of these songs, it was banned from airplay for undermining the righteousness of racial separation which the apartheid government believed in.

In 1980, Steve Kekana released “Colour me Black”, calling for racial unity: “Won’t you colour me black, colour me white, you can colour me any way you like, colour me red, colour me brown, it’s love that makes the world go round.” And four years later, in “People Are People” Depeche Mode questioned racial and cultural prejudice: “So why should it be, you and I get along so awfully. So we’re different colours, and we’re different creeds, and different people have different needs. It’s obvious you hate me, though I’ve done nothing wrong, I’ve never even met you so what could I have done?”

In “One And The Same Heart” Friends First declare that racial separation is anti-biblical: “One and the same heart, yet so far apart, can’t help but wonder what the fuss is about. To a blind man a question of colour, would be so hard to work out, made in the same Godly image, but categorised by skin”. Niki Daly was also critical of apartheid separation – in “Sunny S. Africa”. The song, with an oft-repeated chorus of “That’s the way it is in sunny South Africa”, ends with the ‘chameleon dance’: a review of the number of people in South Africa who had, in the previous year, officially changed their racial classification, statistics which were published in the government gazettes. While the statistics Daly reels off reveal that many people changed from one race to another, he ends by noting that ‘No blacks became white and no whites became black’. Thus was white superiority indelibly stamped in the statute books and upheld by the SABC censors.

In “Together As One” Lucky Dube asked, “Too many people hate apartheid, why do you like it?” and then called for unity “Hey you Rastaman, Hey European, Indian man, we’ve got to come together as one.” It was not a vision shared by the SABC censors who promptly gave it the same treatment as all the other songs on this mixtape, by banning it from airplay.

Although the SABC continued to censor music until 1996, when the Broadcasting Complaints Commission came into being, they stopped taking issue with songs about togetherness by the time the ANC was unbanned in early 1990. That’s about the time when a wave of South African musicians embarked on all forms of cross-cultural musical expressions and collaborations, none of which were banned from airplay for promoting racial and cultural unity. Perhaps a theme for a future mixtape …

Playlist

- Colour Me Black, Steve Kekana, 00:00:00

- Together As One, Lucky Dube, 00:03:21

- One Love, Bob Marley & The Wailers, 00:07:27

- Melting Pot, Blue Mink, 00:10:04

- Black And White, Three Dog Night, 00:13:47

- Why Can’t We Be Friends, War, 00:17:30

- Society’s Child, Janis Ian, 00:21:03

- Get Together, Julie Felix, 00:24:09

- Come Together, Gladys Knight & The Pips, 00:26:44

- All Kinds Of People, Burt Bacharach, 00:30:01

- Basin Street Blues, Dorsey Brothers, 00:32:46

- Black Boys, Cast of ‘Hair’, 00:35:50

- One And The Same Heart, Friends First, 00:39:24

- Girl With Combination Skin, Boy George, 00:44:16

- Sunny South Africa, Niki Daly, 00:49:46

- Why Can’t We Live Together, Timmy Thomas, 00:55:18

- Mama Coco, Gino Vanelli, 00:59:45

- Tribal Fence, Rabbitt & Margaret Singana, 01:02:45

- Do It Anyway, John Miles, 01:06:22

- People Are People, Depeche Mode, 01:09:02