This week we remember the victims of the Sharpeville Massacre which took place on the 21st March 1960. 69 protesters were killed and 189 injured by the apartheid police, in response to a gathering of approximately 7000 people who assembled at a Sharpeville police station to protest the government’s heinous pass law policy. In South Africa the 21st of March is honoured as Human Rights Day and is a public holiday. For this mixtape we have put together 21 songs which remember human rights abuses, Sharpeville in particular, and which call for (equal) human rights.

We begin with Bob Marley and the Wailers’ “Get Up! Stand Up!” which has become an anthem for human rights all over the world, often sung at political concerts with a human rights focus.

Several of the tracks included here refer directly to Sharpeville (sometimes spelt without the ‘e’): Hugh Masekela, Mario Pavone, Big T Commemoration Band, Ewan Maccoll and Peggy Seeger, Black Savage, and Karl Hektor and the Malcouns all recorded pieces which pay direct tribute to the victims at Sharpeville.

The Brixton Moord En Roof Orkes’s “Die Geraamtes In Jou Kas” (“The Skeletons In Your Closet”) and Bester Meyer’s “Die Kind” (“The Child”, based on the famous Ingrid Jonker poem) refer to Sharpeville within the context of the widespread injustices of the apartheid regime.

Miriam Makeba’s “Nonquonqo” (Beware Verwoerd) and Letta Mbulu’s “Nonquonqo” both capture the anti-apartheid government protest sentiments of the post-Sharpeville period. While the former warns Verwoerd’s government of Black protest, the latter grieves the imprisonment of political prisoners after the repressive government’s clampdown in the 1960s.

Juluka’s “Mama Shabalala” and Bob Dylan’s “The Lonesome Death Of Hattie Carroll” remind us how human rights abuses often take place on an individual level, even while we generally think of human rights abuse on a larger scale. Both songs consider the plight of individuals within an oppressive system, the former a fictional case in South Africa, the latter an actual incident from the United States.

Indeed, human rights abuses occur globally, and the mixtape also focuses on human rights abuses more broadly. Billie Holiday’s iconic “Strange Fruit” laments the lynching of black people in the southern states of the United States, while U2’s “Mothers Of The Disappeared” and Sting’s “They Dance Alone” are tributes to the mothers and partners of victims of government repression in Central and South American countries. The victims had been arrested, killed and ‘disappeared’. U2’s song refers to the Madres de Plaza de Mayo, a group of mothers whose children had ‘disappeared’ at the hands of Chilean and Argentinian dictatorships, and to the Comadres, a similar group in El Salvador. Sting’s “They Dance Alone” is dedicated to women related to the ‘disappeared’ in Chile, referring to the way the women danced the Cueca (the national dance) alone, while holding photographs of their loved ones. Both U2 and Sting were inspired to write these songs because of their work with the Human Rights organization, Amnesty. Another artist who has worked closely with Amnesty is Peter Gabriel, who wrote “Wallflower” as a tribute to political prisoners around the world. Gabriel’s chilling words are both a tribute to political detainees and a reminder of the human rights abuses carried against them:

Hold on, you have gambled with your own life

You faced the night alone

While the builders of the cages

Sleep with bullets, bars and stone

They do not see the road to freedom

That you build with flesh and boneThough you may disappear, you’re not forgotten here

And I will say to you, I will do what I can do

The mixtape ends with four songs which advocate human rights in one way or another: by Rhiannon Giddens’ version of “Freedom Highway”, Daweh Congo’s “Human Rights And Justice”, “Equal Rights” by Peter Tosh and finally, Laurel Aitken’s interpretation of the USA folk protest song, “We Shall Overcome”.

As we listen to this selection, we are reminded of music’s capacity to mourn and document human rights abuses, and its ability to capture emotional sentiments which in turn can draw people together as they fight against repressive governments the world over.

- Get Up! Stand Up! – Bob Marley & The Wailers

- Sharpville – Hugh Masekela

- Sharpeville – Mario Pavone

- Tears For Sharpeville – Big T Commemoration Band Featuring Vuyelwa Luzipo

- Strange Fruit – Billie Holiday

- The Ballad Of Sharpeville – Ewan Maccoll And Peggy Seeger

- Ndodemnyama – Miriam Makeba And Harry Belafonte

- Nonquonqo – Letta Mbulu

- Mama Shabalala – Juluka

- The Lonesome Death Of Hattie Carroll – Bob Dylan

- Sharpeville – Black Savage

- Sharpville Massacre – Karl Hector & The Malcouns

- Die Kind – Bester Meyer

- Die Geraamtes In Jou Kas – Brixton Moord En Roof Orkes

- They Dance Alone – Sting

- Mothers Of The Disappeared – U2

- Wallflower – Peter Gabriel

- Freedom Highway – Rhiannon Giddens

- Human Rights And Justice – Daweh Congo

- Equal Rights – Peter Tosh

- We Shall Overcome – Laurel Aitken

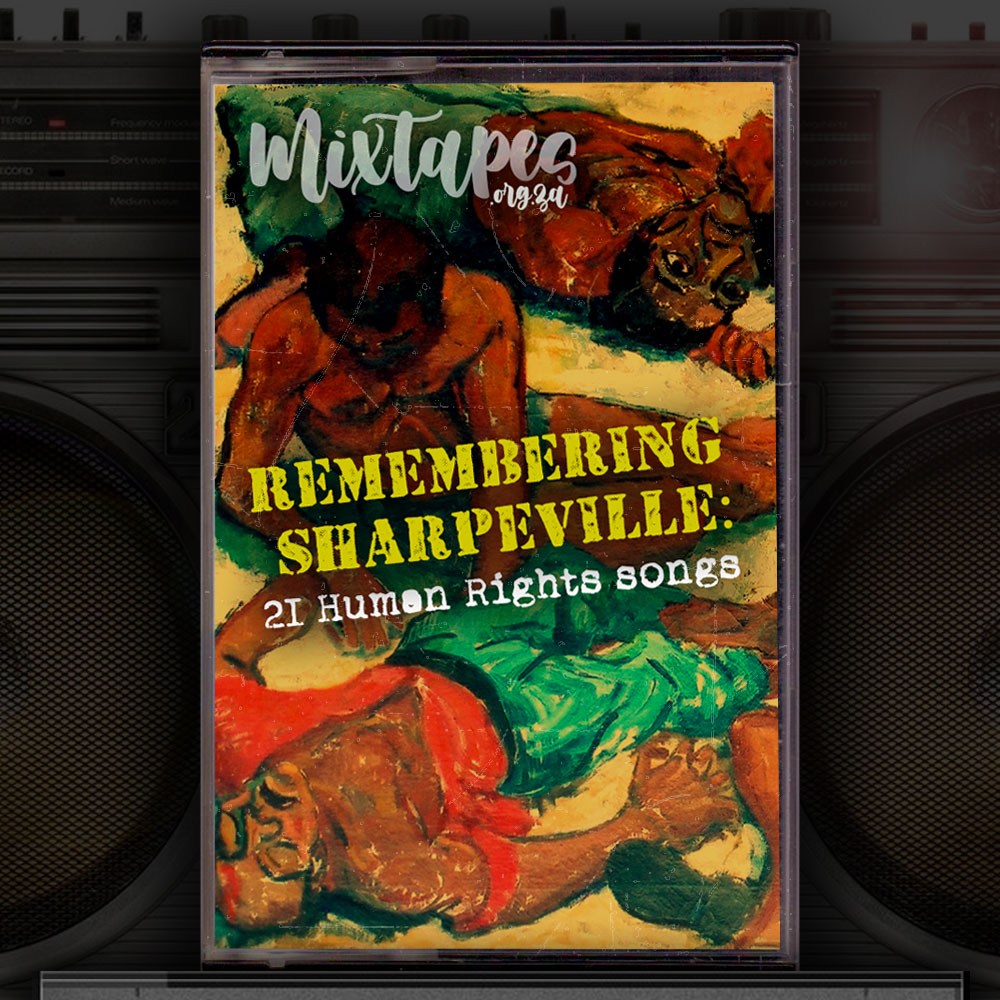

The cover art features an extract of a painting depicting the Sharpeville massacre by Godfrey Rubens which hangs in the South African Consulate in London.